Cover of Harper's Weekly 9/20/1862 Image courtesy of sonofthesouth.net

The American Civil War was a watershed event in the history of American journalism. Mitchell Stephen’s book “A History of News” says that the “Civil war does more for the development of American Journalism than any other event.” In a war that is regarded as the most important event in defining the United States as a nation, war reporting would soon become an issue that concerned all Americans-whether they be Confederate or Union. During this conflict, war reporting created and satisfied a culture that was thirsty for news.

The morale of the populace in both North and South rose and fell with newsprint. News of the victory of an army, spread via telegraph from distant battlefields, into cities, and made it’s way onto newsprint shortly thereafter. For the first time in human history we see people finding out the fate of their respective armies in less than twenty-four hours, compared with the Battle of Concord and Lexington 80 years earlier when it took news anywhere from two days to a month to reach other parts of the nation. Casualty lists kept families at home promptly informed of the status of their loves ones. War reporting kept the populace tied together emotionally.

While war reporting was usually accurate in reporting the outcomes of battles and casualty lists, correspondents could still be quite unreliable and often times just plain wrong. George Townsend is a great example of a person who allowed imagination, rumor, and fact to become mixed up quite easily. He describes the drab morale of Union soldiers who early on in the war had actually not lost quite so much hope in their cause, as he vividly describes.

Townsend was one of the sixty-three reporters working for the now defunct New York Herald, which was quite sensationalistic in its early stages to begin with. These sensational correspondents were simply trying to get their story out there in the quickest fashion possible in order to appease their bosses. Speaking of the Battle at Cheat Mountain some twenty years after the fighting had ceased, Confederate soldier Sam Watkins remembers, “I only know what the newspapers said about it, and you know that a newspaper always tells the truth.” Even the soldiers cynacism towards the sensational press of the Civil War era is evident in personal memoirs, decades after the fighting. There were, however, some decent publications in the days of the Civil War.

Harper’s Weekly started in the years just preceding the Civil War and provides excellent examples of war correspondence. While the magazine had origins in printing shorts and fiction, it soon came to embrace issue of the Civil War filling its pages with stories, illustrations, and editorials regarding all subjects related to America’s greatest conflict. Harper’s Weekly remains a great testament to the ingenuity of American journalists in satisfying that thirst for news many citizens had.

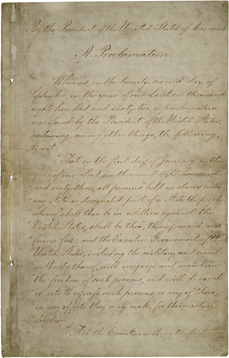

When it came to a turning point in the war, newsprint came in to fill it’s position as facilitator of truth and rumor. News of The Emancipation Proclamation was issued throughout the various newspapers, first in September of 1862 and later in January of 1863. Slaves freed in the south no longer had to rely on sketchy word of mouth, rather they had hard evidence of their freedom printed in black and white.

Emancipation Proclamation Imagecourtesy of archives.gov

As it can be seen, the American Civil War did much to develop journalism in the United States. Victory and death were discovered daily and the telegraph came to prominence in war strategy and reporting. Sensationalism ruled correspondents and editors believed that whoever could get the news out fastest would make the most money. To discuss all of the changes brought about in American journalism due to the Civil War would be quite a lengthy read. Simply put, the war increased a thirst for news due to technological developments, led to a rise in sensationalism, and ushered the newspaper forward to replace word of mouth as a primary means of news.

Leave a response