Although the rise of print journalism helped to improve the accuracy of news being spread, it didn’t escape the influence of storytelling/word of mouth completely, especially about international affairs. Mitchell Stephens refers to this phenomenon in our text as “The Haze”, a factor that causes events out of the region’s range “to be seen in soft focus” (pg. 207).

The haze was particularly prominent when it came to more immediate news such as the death of an international leader or the end of a war or battle. News of these events would come back with travelers, their stories becoming the facts on which papers would base their coverage. The velocity of this information, although improved, would cause months to pass before the event was covered in the newspapers. Due to the speed and nature of how international information traveled, it was easy for it to transform and lead to false or misleading reports.

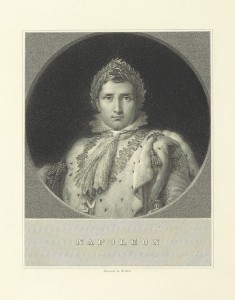

One of the most striking examples of the haze affecting the spread of international news to the United States is the fall of Napoleon. As the condition of Napoleon’s empire began to deteriorate, a similar effect occurred for the news received from the region. In the weeks and months following, false or exaggerated reports thickened the haze surrounding the situation. Conflicting reports continued, including that Napoleon had regained control of his empire rather than passing, and caused uncertainty around what had actually occurred. It wasn’t until much later that Americans were able to gain access to more accurate information about this situation.

The haze would continue to affect the spread of international news for some time during the early 19th century until new inventions such as the steam powered printing press and telegraph once again revolutionized and improved the velocity and accuracy of information.

Leave a response