We’ve all seen it. On telephone booths. In subway tunnels. Sprawled across street signs. Such a phenomenon seems almost inescapable. Since its explosion in the 1970s, the increasing popularity of graffiti as an art form has won commercial success for its artists and earned a legitimate presence in pop culture and the contemporary art world.

There have been many great graffiti artists. Cool Disco Dan. Poster Boy. Banksy. Many fought the government or society or “the Man.” Many sprayed their paint cans for peace, justice or even equal rights. BUT, some dared to stencil for the salvation of our minds, for the redemption of our psyche, and for the freeing of our consciousness. In a world that seems to do anything but help the innocent, these few can be seen as saviors of humanity, as liberators.

Enter John Tsombikos. AKA BORF.

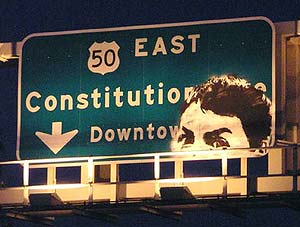

Tsombikos, at the age of 19, spent three months in jail for a graffiti campaign that lasted from 2004 to 2005, during which he carried out one of the most popular attacks on DC’s (not to mention, the world’s) social scene. BORF, Tsombikos’ tag name, turned into a normal part of the public’s life as he began regularly painting his way across the city’s concrete walls. This four letter word eventually became ubiquitous around the Northwest quadrant of Washington, and ranged from simple tagging to complete sentences to two-color stencils to the massive defacement of an overhead exit sign on the Roosevelt Bridge. Aside from DC alone, his graffiti is also reported to have appeared in New York, San Francisco, Raleigh, Rome, and other places.

So what can you say? The kid’s prolific.

But, what else is there to know about Tstombikos? What makes him tick? What inspired his operation, and what was he fighting for? What, if anything, is the meaning of BORF?

“The truth is, BORF means a lot of things,” Tsombikos said, as he gently poked at his vegan salad while being interviewed on a patio beside Deli Italiano, a local hot spot in his hometown of Great Falls, VA. “Part of it was my way of coping with the suicide of my best friend in high school, Bobby Fisher. I don’t want to make him out to be a victim or make him sound helpless or anything, but he was a true casualty of society.”

Tsombikos pulled a fork full of salad up to his mouth and took a bite. He chewed for a minute, then got back to what he was saying. “In this crazy world of ours, where all men are supposed to have six-packs, where women are urged to weigh 100 lbs, and where everyone dreams of owning a house, a picket fence, and 2.5 kids, it’s kind of hard not to get depressed,” he said, swallowing. “We’re all jacked in, you see, and some people are too innocent or good-natured to deal with that. In other words, we’re all subliminally mindfucked by American culture, and particularly the media. Bobby saw this and it tortured him.”

Tsombikos put his fork down and took a big swig of his coconut juice. He wiped his mouth with a napkin, then continued. “Through graffiti, I was simultaneously coping with Bobby’s death while getting revenge on the system,” he added. “The term is culture-jamming.”

Culture jamming is a tactic used by rebels like Tsombikos to disrupt or subvert media culture and it’s mainstream institutions, and in particular, to sabotage corporate advertising.

With his salad nearly gone, and his juice halfway finished, he started up again.

“My message was simple, yet remarkably complex. It was a word without a definition. While most people think they have their lives figured out, or think they understand everything, I wanted to confuse them. I wanted to give them something that would wake them up, pull them out of the system, and make them go ‘what the fuck?'”

Because confusion was one of the main staples of Tsombikos’ crusade, people began to pay attention. “His shit was everywhere,” says Lennox Greeley, a Georgetown University student, friend of Tsombikos, and long-time DC resident. “I’d see it on the way to class, on the way to work, on the way to dinner. Most of what he said made no sense, but it was funny.”

So, what did BORF say?

Some of the things Tsombikos tagged were as follows. “BORF is not caught. BORF is many. BORF is none. BORF is waiting for you in your car. BORF is in your pockets. BORF is running through your veins. BORF is naive. BORF is good for your liver. BORF is controlling your thoughts. BORF is everywhere. BORF is the war on boredom. BORF annihilates. BORF hates school.” And of course, a personal favorite of Tstombikos, “BORF writes letters to your children.”

“Think what you want,” Greeley asserted, grinning, “but BORF had a sense of humor.”

Tsombikos took his hands and smeared them on his paint-stained jeans. He finished his salad and his juice, and seemed satisfied. “I guess when it all comes down to it, BORF was my way of making a difference in the world. I wanted to have an impact, to provoke a change,” he went on to say, maintaining eye contact. “You’d be surprised what one man can do.”

Indeed, BORF, indeed.

Leave a response