The opening chapter of Michael Schudson’s Discovering the News is basically a celebration of the brilliance that was the penny press. Schudson talks about how the penny press forever changed the face of journalism and of the dissemination of news, beginning in the early 1830’s. Schudson called the penny press a “revolution” for news.

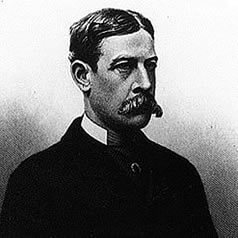

Bennett published NY Herald

Schudson also discusses, towards the back-end of his opening chapter, about a man named James Gordon Bennett. Bennett was the publisher of a paper written for middle-class readership called the New York Herald. With that said, the bulk of the chapter was on the penny press and how it changed the face of journalism.

Before I tell you about the background of the penny press I think I should answer the question you are all asking yourselves. “When did the first penny paper come about and what was it called?”

Well, I hope you aren’t in my history of journalism class if you are asking that. If you are, you didn’t pay enough attention in class because we talked about it at least 17 times this semester. But hey, this is a public blog and you may not be in our class, so I will answer the question for you anyway.

The New York Sun was the first penny paper. It was published in 1833 by Benjamin Day. But why was this so important and why does Schudson love the penny press as much as Jack loved Rose? Why is it important enough to have been the focal point of the first chapter of his wildly popular book?

Schudson says that the penny press was revolutionary in that it turned editorial fluff into factual news. You see, before it came along newspapers were distributed by publishers who were linked to politicians and wealthy dignitaries who were looking to spread their opinions. As you can probably assume, the papers that were being distributed typically showed great bias.

They were also far more expensive than the penny papers, and as a result were available to future papers. In the pre penny press days you would have had to cough up six cents to buy yourself a paper. What’s worse was that even if you were able to dig up six cents by looking through your couch cushions and emptying out your piggy bank, you still might not have been able to get yourself a paper.

Many papers were only distributed based on subscriptions. So you had to have a steady six cents that you could shell out for a fresh issue of the paper. That was not the case for most people back in the early part of the 19th century.

As you might have already assumed, penny papers were sold each day for one penny. They were walked around town by newsboys and distributed to anybody and everybody who wanted to pay a cent for that day’s news. You didn’t have to have subscription to the paper, you just had to have a penny, and a hunger for news.

As an aside, (If Wilbon can do it why can’t we?)… Schudson did not go into detail about the newsboys in his chapter. I, however, would like to talk about them for just a moment. When I was a child I used to watch a movie called “Newsies” all the time. In this movie, newsboys sold papers for Pulitzer and Hurst, and eventually decided to strike because they didn’t have any of the rights they thought they deserved.

“Newsies” was an epic film that culminates with the newsboys fighting against the ‘goons’ that the paper companies sent after them. It ties in very well to our class and I think we should have watched it already. Since we haven’t, I’ve found a clip from the film that I want you to watch. Remember, this relates to my blog and to this class very well because the newsboys are selling penny papers in the clip. So don’t feel bad about watching the opening scene of the newsies.

Schudson’s first chapter attributes a great deal of the success of penny papers to the fact that their circulations quickly surpassed that of their six-cent rivals. The spike in circulations, according to Schudson, should be chalked up to the fact that the papers were cheaper and that people were now buying them day-in and day-out.

Another plus that the author pointed out about the penny paper was that most of them were independently produced. This meant that the publishers behind them weren’t trying to satisfy any wealthy politician by promoting their views or by leaning towards one political side or another. They were more “centered,” which is part of the reason why Schudson said penny papers turned “editorials” more “factual.”

Schudson stated that penny papers succeeded in their advertising strategies by being less picky than their predecessors. The biggest difference in advertising between penny papers and the newspapers that were around before them was the idea that the advertisements in the penny papers were geared towards a more common group of people. They weren’t just going to advertise “to the elite,” but instead to the “people who had a penny.”

At about this time, the nation was becoming more literate. I suppose this is something of a chicken-or-the-egg question as to which happened first, but Schudson states that the spread of literacy throughout the nation inspired the growth of newspapers and the journalism field as a whole.

Leave a response